When you’re learning about lipids and fats, understanding how to describe how phospholipids are different to triglycerides is crucial for grasping basic biochemistry. These two molecules might seem similar at first glance—they’re both lipids, they both contain fatty acids, and they’re both essential to life. But dig deeper, and you’ll discover they’re fundamentally different in structure, function, and how your body uses them. Think of it like comparing a basic tool to a specialized one in your workshop: both are useful, but they’re designed for completely different jobs.

Table of Contents

- Basic Structure Differences

- Molecular Composition Breakdown

- The Glycerol Backbone

- Fatty Acid Attachment Methods

- Hydrophobic vs Hydrophilic Properties

- Biological Functions Compared

- Energy Storage and Metabolic Roles

- Membrane Structure Importance

- Solubility and Behavior in Water

- Health Implications and Dietary Impact

- Frequently Asked Questions

Basic Structure Differences

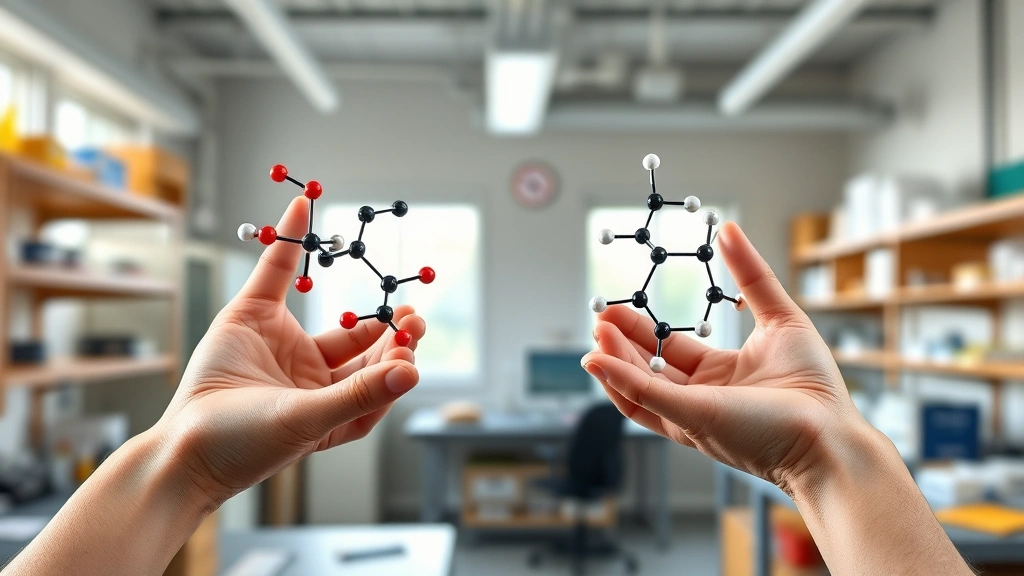

Let’s start with the foundation. Triglycerides and phospholipids both begin with a glycerol molecule—a three-carbon backbone. But here’s where the paths diverge dramatically. Triglycerides are relatively straightforward: three fatty acids attach to that glycerol backbone through ester bonds, and that’s it. You’ve got a complete molecule with no additional components. Phospholipids, on the other hand, follow a different blueprint. They start with the same glycerol backbone, but only two fatty acids attach to it. The third position? That’s where things get interesting. Instead of another fatty acid, you get a phosphate group (PO₄³⁻) bonded to various other molecules like choline, ethanolamine, or serine. This seemingly small difference creates molecules with entirely different personalities and purposes.

Molecular Composition Breakdown

To truly describe how phospholipids are different to triglycerides, you need to understand their elemental makeup. Triglycerides contain carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen—that’s it. Simple. Their formula follows a predictable pattern based on the fatty acids involved. Phospholipids contain those same elements but add phosphorus and often nitrogen to the mix. This additional phosphorus is the signature component that gives phospholipids their name and their unique properties. According to research from the National Institutes of Health, this phosphate group fundamentally alters how these molecules interact with their environment. The presence of phosphorus creates a polar region on the molecule, which is absolutely critical for membrane function.

The Glycerol Backbone

Both molecule types share this common starting point: glycerol, a simple three-carbon sugar alcohol. Imagine this as the frame of your project—it’s the structural foundation everything else builds on. In triglycerides, all three hydroxyl groups (-OH) on the glycerol get occupied by fatty acid chains through esterification. It’s a complete takeover: all three positions filled, all three bonds formed. Phospholipids use this same glycerol backbone but approach it differently. Two of the three hydroxyl groups still get fatty acids, maintaining that hydrophobic tail region. But that critical third position remains open for the phosphate group and its associated polar head. This distinction is why phospholipids are sometimes called “incomplete” triglycerides, though that’s somewhat misleading since they’re actually specialized for different work.

Fatty Acid Attachment Methods

Both triglycerides and phospholipids attach their fatty acids through the same chemical mechanism: esterification. This creates an ester bond between the carboxyl group of the fatty acid and the hydroxyl group on glycerol, releasing water in the process. The difference lies in quantity and positioning. Triglycerides form three ester bonds—one at each position on the glycerol molecule. This triple bonding makes them very stable and very hydrophobic (water-repelling). Phospholipids form only two ester bonds in the same way, at the first and second positions on glycerol. The third position gets a phosphodiester bond instead, which connects the phosphate group. This means phospholipids have two fatty acid tails (hydrophobic) but also have a phosphate-containing head group (hydrophilic, or water-loving). It’s this asymmetry that makes phospholipids amphipathic—having both water-repelling and water-attracting regions.

Hydrophobic vs Hydrophilic Properties

Here’s where the practical differences become obvious. Triglycerides are almost entirely hydrophobic. Their three fatty acid chains create a completely nonpolar molecule that absolutely hates water. Drop a triglyceride in water and it’ll cluster with other triglycerides, forming droplets that keep water out. This makes them perfect for energy storage—they pack together tightly and don’t interact with the aqueous environment inside cells. Phospholipids present a split personality. The fatty acid tails are still hydrophobic, but that phosphate head group is intensely hydrophilic. It loves water and will interact readily with aqueous solutions. This dual nature—having both hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions—is called amphipathicity, and it’s the secret to why phospholipids can do something triglycerides absolutely cannot: form membranes. The National Cancer Institute emphasizes this property when explaining cellular structure, as it’s fundamental to how cells maintain their integrity.

Biological Functions Compared

The structural differences directly translate to different biological roles. Triglycerides are your body’s energy storage champions. When you eat food and your body has enough energy for immediate needs, it converts excess calories into triglycerides and stores them in adipose tissue (fat cells). They’re compact, energy-dense molecules—each gram provides 9 calories compared to 4 calories per gram for carbohydrates or proteins. When you need energy later, your body breaks down these triglycerides through lipolysis and uses the fatty acids for fuel. Phospholipids have almost nothing to do with energy storage. Instead, they’re the architects of cellular membranes. Every cell in your body is surrounded by a phospholipid bilayer—a double layer of phospholipids arranged with their hydrophobic tails pointing inward (away from water) and their hydrophilic heads pointing outward (toward water). This arrangement creates a barrier that protects the cell while allowing selective passage of molecules. Phospholipids also play roles in signaling, inflammation, and blood clotting.

Energy Storage and Metabolic Roles

Triglycerides dominate the energy storage landscape. Your liver synthesizes them from excess carbohydrates and proteins, and your adipose tissue stores them in virtually unlimited quantities. They’re the reason a pound of fat stores more than twice the energy of a pound of muscle. During fasting or exercise, hormones like epinephrine and glucagon trigger hormone-sensitive lipase, which breaks triglycerides down into glycerol and free fatty acids. These fatty acids then travel through your bloodstream to tissues that need energy, where they’re oxidized in mitochondria through beta-oxidation to produce ATP. Phospholipids participate in metabolism but not as energy sources. Your body can break down phospholipids to access their fatty acids, but this isn’t their primary purpose. Instead, phospholipids are continuously recycled and rebuilt as cells divide and membranes are repaired. The phosphate groups can be reused for energy production (ATP synthesis) or incorporated into other molecules, but the phospholipid itself is meant to persist as a structural component.

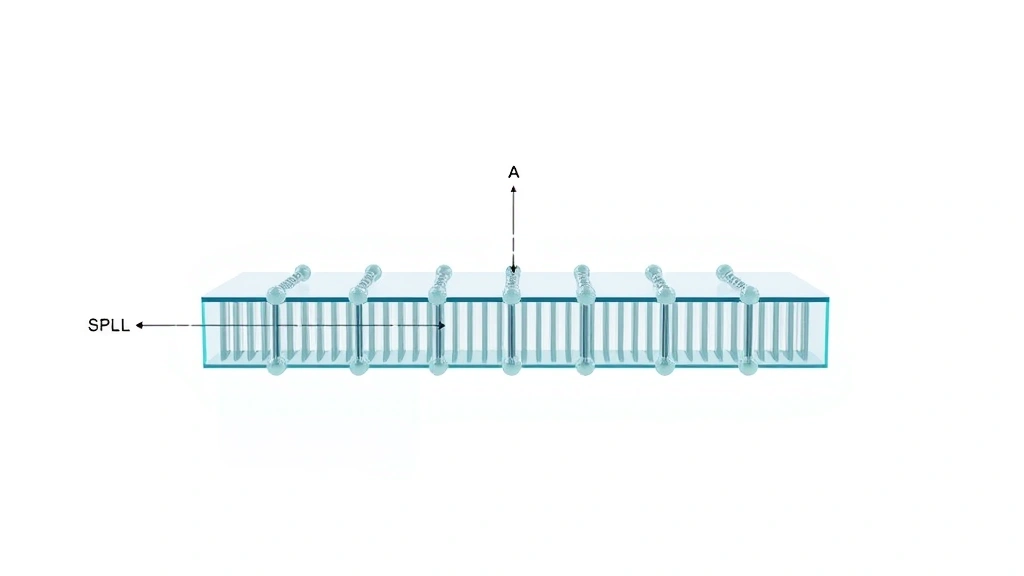

Membrane Structure Importance

This is where phospholipids truly shine, and triglycerides simply cannot compete. The phospholipid bilayer is the fundamental structure of all cell membranes. It’s not just a simple barrier—it’s a sophisticated, dynamic structure that regulates what enters and exits the cell. Triglycerides could never perform this function because they’re completely hydrophobic. They’d either clump together in the aqueous environment or dissolve in nonpolar solvents, but they couldn’t create a stable barrier between water and the cell interior. Phospholipids, with their water-loving heads and water-repelling tails, spontaneously arrange themselves into bilayers when placed in water. The hydrophobic tails cluster together in the middle, shielded from water, while the hydrophilic heads face the aqueous environment on both sides. This creates a semipermeable barrier—small, nonpolar molecules can slip through, but large or charged molecules cannot without assistance. Embedded in this phospholipid bilayer are proteins that perform countless functions: transport, signaling, recognition, and catalysis. Without phospholipids, cells as we know them simply couldn’t exist.

Solubility and Behavior in Water

Drop a triglyceride into water and observe what happens: it won’t dissolve. It’ll form a droplet, clustering with other triglyceride molecules to minimize contact with water. This is why triglycerides need special transport proteins (lipoproteins) to travel through your bloodstream. They’re packaged into VLDL (very low-density lipoprotein), LDL (low-density lipoprotein), or chylomicrons—essentially tiny spheres with a phospholipid coating on the outside (hydrophilic heads facing the water) and triglycerides packed inside (hydrophobic cores). Phospholipids behave differently. While they won’t dissolve like salt or sugar, they’re amphipathic enough to form stable structures in water. They naturally assemble into bilayers, micelles, or liposomes depending on conditions. This greater compatibility with aqueous environments means phospholipids don’t need the same level of special packaging for transport. According to research from the National Institutes of Health, this solubility difference is crucial for understanding lipid transport and metabolism in living organisms.

Health Implications and Dietary Impact

Understanding these differences has real health consequences. Triglycerides in your bloodstream are a key health marker. Elevated triglyceride levels correlate with increased risk of heart disease, stroke, and metabolic dysfunction. When you eat a diet high in refined carbohydrates and sugar, your liver converts these to triglycerides, raising your blood levels. Reducing refined carbs and increasing exercise helps lower triglycerides. Phospholipids, by contrast, aren’t typically measured in standard blood work because they’re not an energy storage molecule and don’t accumulate dangerously in the blood. Your body maintains relatively stable phospholipid levels because they’re essential for cell membrane integrity. However, the fatty acids that make up phospholipids matter for health. Phospholipids containing omega-3 fatty acids (like phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylcholine with DHA/EPA) have been associated with improved cognitive function, reduced inflammation, and better cardiovascular health. This is why fish oil supplements and fatty fish consumption are recommended—you’re getting phospholipids and triglycerides rich in beneficial omega-3 fatty acids.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can your body convert triglycerides into phospholipids?

Yes, your body can perform this conversion, though it’s not the primary pathway. When you consume triglycerides, your body can break them down into glycerol and fatty acids. These components can then be reassembled into phospholipids when the body needs to build or repair cell membranes. However, this requires additional components like phosphate groups and nitrogenous bases, which come from other dietary sources or are synthesized from existing molecules. The conversion is possible but energetically expensive, so your body prefers to obtain phospholipids directly from food sources like eggs, fish, and nuts.

Why can’t phospholipids store energy like triglycerides?

Phospholipids could theoretically be broken down for energy—their fatty acid components contain the same caloric density as those in triglycerides. However, using phospholipids for energy would compromise cell membrane integrity. Your body prioritizes maintaining cell structure over accessing this energy source. Additionally, phospholipids are more metabolically expensive to synthesize, so your body wouldn’t waste energy breaking them down when abundant triglycerides are available for fuel.

What happens if you don’t have enough phospholipids?

Without adequate phospholipids, cell membranes become compromised. They lose flexibility, integrity, and functionality. Cells can’t regulate what enters and exits properly. In severe deficiency, cells would die. This is why certain phospholipids, like phosphatidylcholine, are considered essential nutrients. Your body can synthesize some phospholipids from scratch, but obtaining them from food (eggs are particularly rich in phosphatidylcholine) is more efficient.

Are all triglycerides bad for your health?

Not necessarily. Triglycerides themselves aren’t inherently harmful—they’re your body’s primary energy storage mechanism. The problem arises with excessive levels in the bloodstream, which correlate with metabolic dysfunction. The type of triglyceride matters too. Triglycerides composed of shorter-chain fatty acids or unsaturated fatty acids are generally healthier than those made from long-chain saturated fats. Additionally, triglycerides from whole foods (like nuts or avocados) come packaged with fiber, vitamins, and minerals that support health, whereas refined sources (like sugar and processed foods) lack these benefits.

How do cells regulate phospholipid composition?

Cells actively manage their phospholipid composition through selective synthesis and incorporation. They can modify existing phospholipids by swapping out fatty acid chains or altering the head group. This allows cells to adjust membrane fluidity, permeability, and functionality based on their needs and environmental conditions. For example, cells in cold environments incorporate more unsaturated fatty acids into their phospholipids to maintain membrane flexibility, while cells in warm environments use more saturated fatty acids for stability.

Conclusion

To describe how phospholipids are different to triglycerides is to understand two fundamentally different molecular designs serving completely different biological purposes. Triglycerides are energy storage specialists—three fatty acids on a glycerol backbone, completely hydrophobic, perfectly designed to pack together and store maximum energy in minimum space. Phospholipids are membrane architects—two fatty acids plus a phosphate group on a glycerol backbone, amphipathic, perfectly designed to form the bilayers that define cellular compartments. The structural difference is subtle (one fatty acid versus a phosphate group), but the functional consequences are profound. You cannot use phospholipids for energy storage, and you cannot build cell membranes from triglycerides. Each molecule is exquisitely specialized for its role. Understanding this distinction isn’t just academic—it explains why your body handles these molecules differently, why dietary choices affect your health in specific ways, and how the remarkable organization of life itself depends on these two very different types of lipids working in harmony.