Learning how might you add keystone species to the concept map is fundamental for anyone studying ecology, environmental science, or ecosystem dynamics. Whether you’re a student tackling a biology assignment or an educator designing educational materials, understanding how to properly integrate keystone species into your concept mapping process transforms how you visualize ecological relationships and dependencies.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Keystone Species Basics

- Concept Map Fundamentals

- Identifying Keystone Species First

- Positioning Keystone Species Centrally

- Drawing Connecting Lines Strategically

- Using Visual Hierarchy Effectively

- Digital Tools for Concept Mapping

- Testing Your Map’s Accuracy

- Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Practical Examples in Action

- Frequently Asked Questions

Understanding Keystone Species Basics

Before you can effectively add keystone species to your concept map, you need to genuinely understand what they are. A keystone species is an organism whose impact on its ecosystem is disproportionately large relative to its abundance. Think of it like the keystone in an arch—remove it, and the entire structure collapses.

Keystone species maintain ecosystem balance through their unique ecological roles. Sea otters, for example, control sea urchin populations, which prevents overgrazing of kelp forests. Without sea otters, the entire marine ecosystem shifts dramatically. Similarly, wolves regulate elk populations, which affects vegetation patterns across entire landscapes. These species aren’t necessarily the most abundant or the largest—they’re just critically important.

The power of keystone species lies in their disproportionate influence. They might represent only a small percentage of total biomass in an ecosystem, yet their presence or absence fundamentally alters community structure and function. This characteristic makes them absolutely essential to include in your concept mapping work, as they represent critical nodes in ecosystem networks.

Concept Map Fundamentals

A concept map is a visual representation showing relationships between different concepts. Unlike a simple list or outline, concept maps display how ideas connect, interact, and depend on one another. They’re hierarchical diagrams with nodes (concepts) connected by lines labeled with relationship descriptions.

The basic structure includes a main concept at the top, with subordinate concepts branching downward and outward. Lines connecting concepts are labeled with linking words that explain the relationship. For example: “predator controls” or “depends on” or “maintains balance in.”

When working with ecological systems, concept maps become particularly powerful because they mirror the actual interconnectedness of nature. Your map should show how organisms, abiotic factors, and processes interact—and keystone species represent critical intersection points where multiple relationships converge.

Identifying Keystone Species First

The first step in adding keystone species to your concept map is identifying which species actually qualify as keystones in your chosen ecosystem. This requires research and critical thinking, not just assumption.

Start by examining your ecosystem’s food web. Look for organisms that have disproportionate effects on their environment. Ask yourself: What happens if this species disappears? If the answer is “the entire ecosystem transforms,” you’ve likely identified a keystone species. If the answer is “another species fills its niche without major disruption,” it’s probably not a keystone.

Research published studies about your specific ecosystem. Scientists have identified keystone species in most well-studied environments. For example, in African savannas, elephants are keystones because they shape vegetation structure. In tropical rainforests, certain frugivorous birds and mammals are keystones because they disperse seeds that maintain forest diversity.

Document which species you’ve identified as keystones and why. This documentation process helps you understand the reasoning that will guide your concept map design. You might discover that what seemed like a keystone species actually plays a more supporting role, or vice versa.

Positioning Keystone Species Centrally

Once you’ve identified your keystone species, position them prominently in your concept map. While concept maps don’t require strict hierarchical positioning like some diagrams, placing keystone species in central or prominent locations helps viewers understand their importance immediately.

If you’re using a traditional top-down hierarchy, place keystone species at a middle level where they can connect both upward to broader ecosystem concepts and downward to specific organisms and processes they influence. This positioning reflects their role as critical connectors within the system.

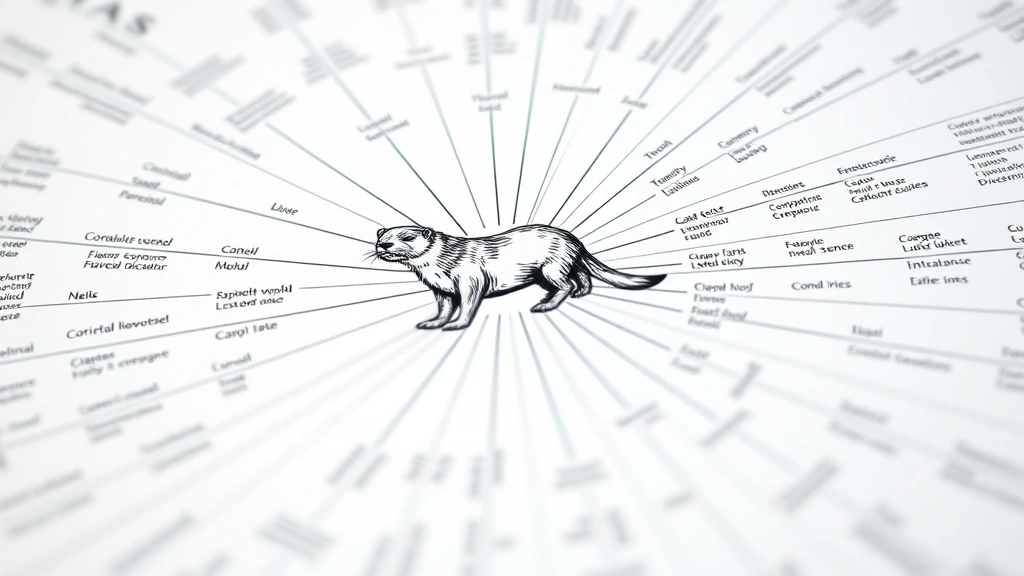

Alternatively, use a radial design where the keystone species occupy the center, with lines radiating outward to all the organisms and processes they directly influence. This visual arrangement makes their central importance unmistakable. It also makes it easier to see at a glance how many connections depend on that single species.

When positioning multiple keystone species, avoid clustering them too closely together. Each needs visual breathing room so that the connections emanating from them remain clear and distinct. If your ecosystem has three keystone species, position them in a triangle or distributed pattern rather than stacked together.

Drawing Connecting Lines Strategically

The connecting lines in your concept map are where the real learning happens. These lines show relationships, and keystone species should have numerous connections radiating from them—more connections than non-keystone species typically have.

Label each connection with a precise relationship descriptor. Instead of just drawing a line between a keystone species and another organism, write “predator of,” “controls population of,” “maintains habitat for,” or “depends on.” These labels transform your map from a pretty diagram into a powerful learning tool.

Keystone species typically have both direct and indirect connections. A sea otter directly preys on sea urchins (direct connection) but indirectly maintains kelp forests (indirect connection through urchin population control). Show both types of relationships on your map. You might use different line styles—solid lines for direct relationships, dashed lines for indirect ones—to make this distinction visually apparent.

Connect your keystone species to abiotic factors too. If a keystone species requires specific water temperatures, soil types, or light conditions, show those connections. This comprehensive approach reveals why keystone species are vulnerable and what environmental changes might threaten them.

Using Visual Hierarchy Effectively

Visual hierarchy helps viewers understand at a glance which concepts matter most. Use size, color, and styling to emphasize keystone species compared to other organisms in your map.

Make keystone species boxes or circles noticeably larger than boxes for other organisms. This size difference immediately signals importance without requiring viewers to count connections. Use a distinct color for keystone species—perhaps red or a bold color that stands out from the rest of your map’s color scheme.

Consider using icons or symbols to represent keystone species. A small image of a sea otter, wolf, or elephant next to the text label makes the concept more concrete and memorable. This visual reinforcement helps students retain the information better than text alone.

Use bold or italic text for keystone species labels, and consider adding a brief descriptor in parentheses, such as “Sea Otter (Keystone Predator).” This explicit labeling removes any ambiguity about why certain species are positioned and styled differently.

Digital Tools for Concept Mapping

While hand-drawn concept maps have value, digital tools offer advantages for adding and modifying keystone species representations. Software like Lucidchart, MindMeister, Coggle, and Piktochart allow you to create professional-looking concept maps with ease.

Google Slides also works well for concept mapping—you can add multimedia elements to your slides to enhance your presentations, including your concept maps. Many educators create concept maps in Google Slides for classroom presentations and student assignments.

When using digital tools, take advantage of their features. Create custom shapes for different types of organisms. Use color coding systematically—perhaps all producers in green, all consumers in red, and keystone species in a distinct highlight color. Use connectors rather than simple lines so that when you move elements, connections stay intact.

Digital tools make it easy to create multiple versions of your concept map. You might create one version emphasizing trophic relationships and another emphasizing energy flow. This flexibility helps you explore different aspects of how keystone species function in their ecosystems.

Testing Your Map’s Accuracy

After adding keystone species to your concept map, test its accuracy by asking critical questions about each connection.

For each line connecting a keystone species to another organism, ask: “Is this relationship accurate? Is it direct or indirect? Would a scientist studying this ecosystem agree with this connection?” If you can’t confidently answer yes, research further or remove the connection.

Check for missing connections. If you’ve identified a keystone species that controls predators, maintains habitat, and provides food for multiple organisms, your map should show all these relationships. A keystone species with only one or two connections probably isn’t truly a keystone, or you’ve missed some important relationships.

Share your concept map with peers or instructors and ask for feedback. Fresh eyes often spot logical gaps or inaccuracies that you’ve missed. Ask specifically: “Do the keystone species I’ve identified make sense to you? Are there important connections I’ve overlooked?”

Test your map’s functionality by using it to answer ecosystem questions. “What would happen if this keystone species went extinct?” should be answerable by following the connections on your map. If you can’t trace the cascading effects through your map, it needs refinement.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Several common mistakes can undermine your concept map’s effectiveness. First, don’t assume that large or abundant species are keystones. The largest animal in an ecosystem isn’t necessarily the most important. Conversely, don’t overlook small organisms—some insects and microorganisms function as keystones in their ecosystems.

Avoid creating concept maps that are too simple. If your keystone species has only two or three connections, you probably haven’t fully explored its ecological role. Keystone species should be connection hubs with multiple relationships radiating outward.

Don’t forget abiotic factors. Keystone species don’t function in isolation from physical and chemical environmental factors. Your map should show how temperature, water, soil, and light affect keystone species and how keystone species modify these abiotic factors.

Avoid unlabeled connections. Every line should have a descriptor explaining the relationship. “Influences” is too vague; “predator of” or “provides nesting habitat for” is specific and meaningful.

Don’t ignore indirect effects. Keystone species often have their most important impacts indirectly. If a keystone predator controls herbivores, which affects plant communities, both the direct predation relationship and the indirect plant community effect should appear on your map.

Layering Your Concept Map

For complex ecosystems with multiple keystone species, consider creating layered concept maps. The first layer shows only the keystone species and the most critical organisms they interact with. Subsequent layers add more detail and complexity.

This layered approach works particularly well for educational settings. Students first master the core concept—which species are keystones and why—before grappling with the full complexity of ecosystem relationships. It also makes your maps more readable by preventing visual clutter.

When creating layers, ensure that each layer remains accurate. The simplified version shouldn’t misrepresent relationships; it should just omit some details. A student using the simplified version should be able to upgrade to the detailed version without learning incorrect information.

Practical Examples in Action

Let’s examine how this works with a real ecosystem. In the Yellowstone ecosystem, wolves function as a keystone species. Your concept map would show wolves at a central position with connections to:

- Elk (direct predation relationship—”preys on”)

- Vegetation (indirect relationship through elk population control—”maintains through predation”)

- Scavengers like ravens and eagles (indirect relationship—”provides food through kills”)

- Riparian ecosystems (indirect relationship—”restores through vegetation recovery”)

- Grizzly bears (indirect relationship—”provides food through carcasses”)

Each connection would be labeled with the specific relationship type. The visual hierarchy would make wolves prominent, and the numerous connections would immediately communicate their keystone status.

In a coral reef ecosystem, coral polyps themselves function as a keystone species. Your map would show connections to fish species that depend on reef structure, algae that live symbiotically within corals, and the broader ecosystem services the reef provides. You’d also show the abiotic factors corals depend on—water temperature, pH, and light—making clear why climate change and ocean acidification threaten this keystone.

Frequently Asked Questions

What if my ecosystem has no keystone species?

Most ecosystems have at least one keystone species, though some highly resilient ecosystems might have multiple species that could fill similar roles. If you’re struggling to identify a keystone species, research more thoroughly. Look for species whose removal would cause the most dramatic ecosystem change. If truly no single species dominates, your concept map might show several species with roughly equal importance—which is itself an important finding.

Can a species be a keystone in one ecosystem but not another?

Absolutely. A species’ keystone status depends entirely on its ecological role in that specific ecosystem. Otters are keystones in kelp forest ecosystems but play a different role in river ecosystems. Always consider the specific ecosystem context when identifying keystones.

How many keystone species should a concept map include?

There’s no fixed number. Most small ecosystems have one to three keystone species. Large, complex ecosystems might have more. Include all the keystone species you can identify and justify based on research. Quality matters more than quantity—a well-researched map with two keystones beats a confused map with five.

Should I include extinct keystone species?

Yes, if you’re exploring ecosystem history or recovery. Showing how an ecosystem functioned when a keystone species was present, versus how it functions now without that species, powerfully illustrates the keystone concept. Use different visual styling (perhaps lighter colors or different line styles) to distinguish extinct species from current ones.

Can humans be keystone species?

Humans function as keystone species in many ecosystems, though the impact is usually destructive rather than stabilizing. If studying human-modified ecosystems, you might include humans as a keystone species to show their disproportionate ecological impact. However, this requires careful framing to avoid oversimplifying human roles.

How detailed should my concept map be?

Start with essential relationships and add detail as needed. For a classroom assignment, a map showing the keystone species, major organisms they interact with, and critical relationships might suffice. For research or professional work, include more detail about indirect effects, abiotic factors, and population dynamics. Your purpose determines appropriate detail level.

Bringing It All Together

Understanding how might you add keystone species to the concept map transforms you from someone who can draw diagrams to someone who truly understands ecosystem dynamics. By identifying keystone species, positioning them prominently, showing their multiple relationships, and using visual hierarchy to emphasize their importance, you create maps that communicate ecological understanding clearly and powerfully.

The process of building a concept map with keystone species forces you to think deeply about ecosystem relationships. You’ll discover connections you hadn’t considered, realize the fragility of ecosystems that depend on single species, and develop a more sophisticated understanding of how nature actually works.

Start with a single ecosystem you know well. Identify its keystone species through research and observation. Build your concept map layer by layer, testing each relationship for accuracy. Share your work with others and refine based on feedback. With practice, you’ll become skilled at creating concept maps that reveal the hidden architecture of ecological systems, with keystone species occupying their rightful place as the critical linchpins holding everything together.