Figuring out how many watts to run a house is one of those practical questions that separates DIY dreamers from actual homeowners who can keep the lights on. Whether you’re planning a backup generator, upgrading your electrical panel, or just curious about your home’s power appetite, understanding wattage is non-negotiable. Let’s walk through this together like we’re standing in your breaker box with a cup of coffee, breaking down the numbers that actually matter.

Table of Contents

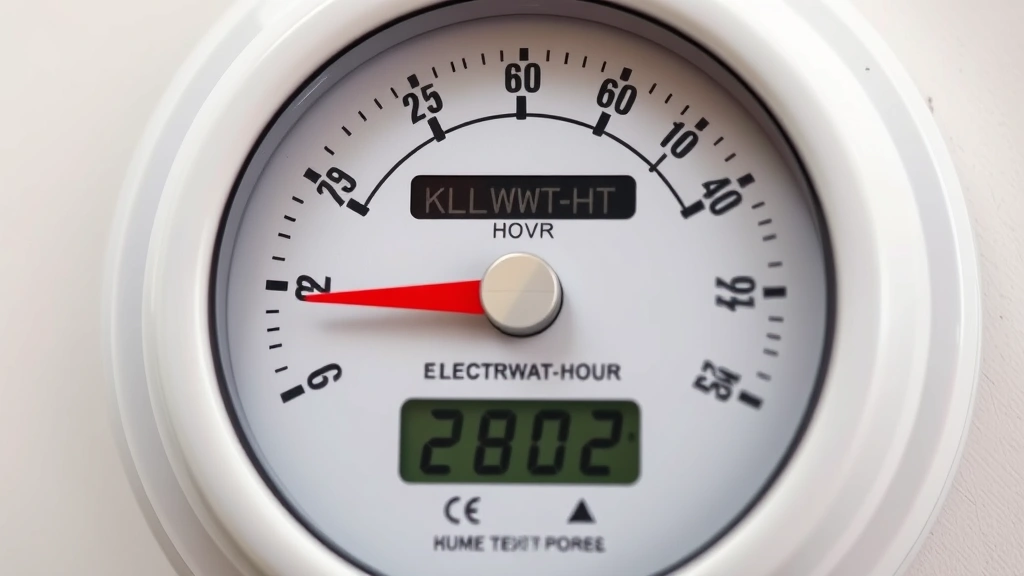

Average Home Power Consumption

Most American homes pull between 19,000 and 38,000 watts during peak usage. That’s a massive range, and here’s why: a tiny apartment in the city operates completely differently than a suburban house with central air and electric heating. The Department of Energy reports the average household uses about 30,000 watt-hours (kilowatt-hours) per day, which translates to roughly 1,250 watts running continuously. But continuous and peak are two different animals entirely.

Your actual peak demand—when everything’s running at once—might hit 30,000-50,000 watts. This is why your electrical service is rated for specific amperage. A standard 200-amp service at 240 volts can theoretically handle 48,000 watts, though you’ll never actually use all of it simultaneously because of demand diversity. That’s the fancy term for “not everything runs at once.”

Peak vs Running Watts Explained

Here’s where most people get confused, and I see it all the time. Running watts are what an appliance uses once it’s up and operating smoothly. Peak watts (or surge watts) are the massive spike when something first starts. Your air conditioner might run at 3,500 watts but demand 5,000 watts for the first second it kicks on. This matters hugely for generators and backup systems.

Think of it like a car accelerating. You need more power to get moving than to cruise at highway speed. Induction motors—which power your AC, refrigerator, and pump—are the worst offenders. They can draw 3-7 times their running wattage just during startup. This is critical information if you’re shopping for a generator or worried about tripping breakers during peak demand.

Major Appliances Breakdown

Let’s get specific, because this is where the rubber meets the road. Here’s what the power hogs in your home actually demand:

- Central Air Conditioning: 3,500-5,000 watts running, 5,000-8,000 watts peak. This is your biggest consumer in summer.

- Electric Heating: 5,000-15,000 watts depending on system size. If you have baseboard heaters, they’re all-in at once.

- Water Heater (Electric): 4,000-5,500 watts. Gas versions use minimal electricity.

- Electric Range/Oven: 2,000-5,000 watts. A full oven at max temp is brutal.

- Refrigerator: 600-800 watts running, 1,200-2,000 peak when compressor starts.

- Clothes Dryer (Electric): 3,000-5,000 watts. One of the heaviest users.

- Dishwasher: 1,800-2,400 watts during heating cycle.

- Microwave: 1,000-1,500 watts.

- Washing Machine: 500-1,000 watts.

- Lighting: 200-600 watts for whole house, depending on bulbs.

Notice how these numbers add up fast? If your AC is running (5,000W), water heater kicks on (4,500W), and someone’s using the dryer (4,000W), you’re already at 13,500 watts and haven’t even started cooking dinner.

Calculate Your Actual Load

Stop guessing. Go grab your latest electric bill—it tells you everything. The kWh number divided by 30 days gives you average daily usage. Multiply by 1,000 to convert to watt-hours, then divide by 24 hours. That’s your average continuous load. But we need peak demand, not average.

Here’s the real method: Walk through your home and list every appliance. Check the nameplate on each one—usually on the back or bottom. It’ll say “Max Watts” or “Amps × Volts.” For items without nameplates, use the chart above. Now here’s the critical part: add up only the items that realistically run simultaneously. You won’t run the oven and dryer at full power while the AC is blasting and the electric water heater is heating. Use demand factors—multiply each appliance by 0.5-0.8 depending on likelihood of simultaneous use.

If you want precision, hire an electrician to do a load calculation. It costs $150-300 and gives you the exact number your local electrical code requires for panel sizing. This is what I’d do if you’re buying a generator or upgrading service.

Generator Sizing for Backup Power

This is where understanding watts becomes absolutely practical. You need a generator rated for your peak demand, not your average. If your home’s peak load is 25,000 watts, a 20,000-watt generator won’t cut it—you’ll overload it the moment your AC and water heater run together.

Most generators come in these sizes: 5,000W, 7,500W, 10,000W, 15,000W, 20,000W, and 25,000W+. Portable units max out around 12,000W. For whole-house backup, you typically need 15,000-25,000 watts. If you’re only backing up essentials (fridge, sump pump, some lights, water heater), 10,000-15,000 watts works.

Pro tip: Don’t forget about surge capacity. A 20,000-watt generator with 25,000-watt surge capacity can handle your AC startup spike. Always buy generators rated 20-30% above your calculated peak load. Running a generator at maximum capacity 24/7 burns it out fast. You want breathing room.

Consider fuel type too. Natural gas generators run continuously as long as your utility supply holds. Portable gasoline generators need refueling. Propane sits in tanks. Diesel is efficient but louder. This affects your total cost of ownership during extended outages.

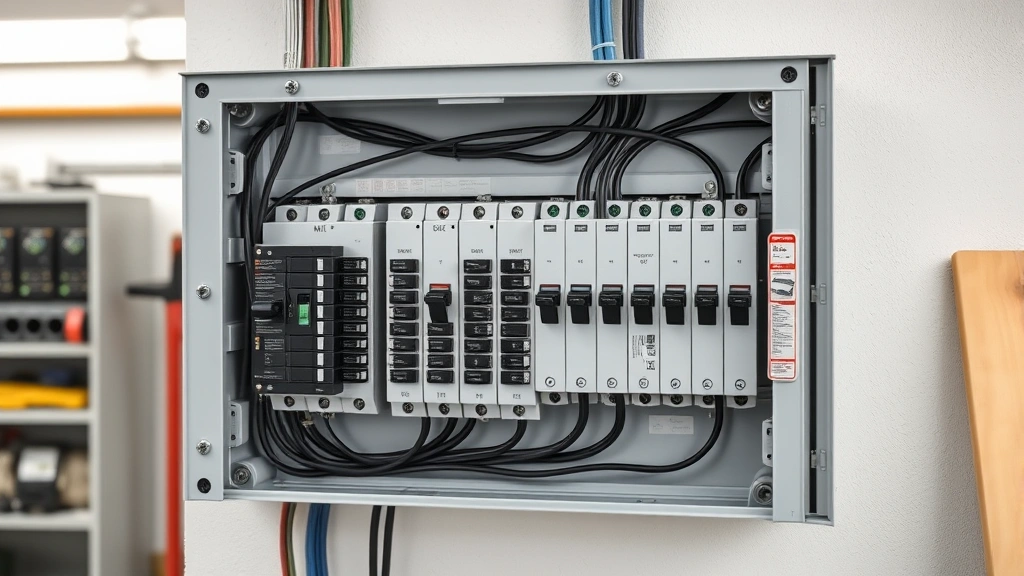

Electrical Panel Upgrades

Your home’s main electrical panel is the gatekeeper. Standard residential service is 100, 150, or 200 amps at 240 volts. That’s 24,000, 36,000, or 48,000 watts respectively. If you’re upgrading to electric heating, adding a Tesla charger, or expanding the house, you might need a panel upgrade.

The calculation is simple: Amps × Volts = Watts. Your 200-amp service = 200 × 240 = 48,000 watts. But here’s the catch: electrical code requires that you size the panel for your calculated load plus 25% headroom. So a 30,000-watt calculated load means you need a 37,500-watt panel minimum, which is a 150-amp or 200-amp service.

Upgrading from 100 to 200 amps costs $1,500-3,000 in most areas, plus permits and inspection. It’s not cheap, but it’s necessary if you’re adding major loads. This is definitely a licensed electrician job—don’t DIY this one.

Seasonal Power Variations

Your power needs swing dramatically with the seasons. Winter in cold climates with electric heating? You’re looking at 40,000+ peak watts when the furnace, water heater, and dryer all run. Summer with central AC? Similar numbers. But spring and fall? You might cruise at 10,000-15,000 watts peak.

This matters for generator selection. If you’re in the South and only care about AC outages, you can size smaller than a Northern homeowner who needs backup for heating. It also affects your electric bill—winter and summer are expensive, shoulder seasons cheap.

If you’re considering solar or a backup battery system, this seasonal variation is crucial. A 10-kW solar system produces way more power in summer than winter. Battery storage needs to account for multi-day winter outages where generation is low.

Future-Proofing Your Power

Here’s the forward-thinking move: size your electrical service and generator for what you might add, not just what you have now. If you’re thinking about an EV charger (7,000-11,000 watts), heat pump (up to 15,000 watts), or pool heater (5,000-10,000 watts), account for it now.

Adding a 200-amp panel when you “might someday” need it costs an extra $500-800. Adding it later when you actually need it costs $2,000-4,000 because you’re retrofitting and possibly upgrading utility service. Same logic applies to generators—buy 25% more capacity than you currently need.

This is especially true if you’re considering home automation, electric heating, or EV ownership. The grid’s moving electric, and your house should be ready.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the difference between watts and kilowatts?

Kilowatts are just 1,000 watts. Your electric bill shows kilowatt-hours (kWh), which is 1,000 watts running for one hour. If your AC uses 5,000 watts for one hour, that’s 5 kWh. Simple conversion: divide watts by 1,000 to get kilowatts.

Can I run my whole house on a 10,000-watt generator?

Probably not if you want everything running. A 10,000-watt generator handles essentials: refrigerator, sump pump, some lights, and maybe a window AC unit. You won’t run your electric dryer, oven, or central AC simultaneously. It’s survival mode, not comfort mode.

How do I know my home’s current electrical service rating?

Look at your main breaker. It’ll say “100A,” “150A,” or “200A.” That’s your service rating. Multiply by 240 volts to get watts. 100A = 24,000W, 150A = 36,000W, 200A = 48,000W.

Do I need a whole-house generator or will a portable work?

Portable generators are cheaper ($1,500-5,000) but require manual setup, fuel management, and extension cords. Whole-house units ($3,000-15,000+) are automatic, run on natural gas or propane, and require professional installation. If you want true peace of mind, whole-house. If you’re budget-conscious, portable works for short outages.

What happens if I overload my electrical panel?

Your breaker trips, cutting power to that circuit. If you keep overloading, the breaker can fail or wiring can overheat, creating fire risk. This is why proper load calculation and panel sizing matter. You’re literally dealing with fire safety.

Is 200-amp service enough for a modern home?

For most homes without electric heating or multiple EVs, yes. 200 amps = 48,000 watts, which handles standard loads with headroom. If you’re adding major electric appliances, you might need more. Have an electrician calculate your specific load.

Can solar panels reduce my power needs?

Solar reduces your grid consumption, but you still need the same electrical service capacity for peak demand. A 10-kW solar system might cover your average daytime usage, but your AC still needs 5,000 watts when it starts. You’re not reducing peak demand; you’re just offsetting consumption. Check out how to clean stainless steel appliances if you’re upgrading to modern energy-efficient models.

Final Thoughts on Home Power

Understanding how many watts to run a house isn’t just an electrical question—it’s about making informed decisions for safety, comfort, and cost. Whether you’re shopping for a generator, planning an upgrade, or just curious about your home’s appetite, the math is straightforward: identify your appliances, calculate peak demand, and size your system accordingly.

Start with your electric bill and nameplate ratings. Do a real load calculation or hire an electrician. Don’t guess on generators or panel upgrades—these are safety-critical systems. And always think ahead: size for what you might add, not just what you have.

Your electrical system is the nervous system of your home. Treat it with respect, get the numbers right, and you’ll have reliable power for whatever you throw at it. If you’re tackling other home projects, understanding your power capacity helps with everything from how long does it take paint to dry on workshop projects to how to program garage door opener installations that need proper circuits. Now go grab that electric bill and start calculating.